Today you’re hearing from Brett Hillman, a biological science technician for the Service’s New England Field Office, as he recounts his work with freshwater mussels at the Service's Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge in Vermont. Brett assists the endangered species biologists and has the great pleasure of working with a wide variety of wildlife. This post is part of a series running all month on freshwater mussels, highlighting their importance to the Northeast landscape and the concerted efforts underway to ensure their future in our waters.

Today you’re hearing from Brett Hillman, a biological science technician for the Service’s New England Field Office, as he recounts his work with freshwater mussels at the Service's Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge in Vermont. Brett assists the endangered species biologists and has the great pleasure of working with a wide variety of wildlife. This post is part of a series running all month on freshwater mussels, highlighting their importance to the Northeast landscape and the concerted efforts underway to ensure their future in our waters.

Before I began my job in the New England Field Office, I will admit that I didn’t have a great appreciation for mussels.

I knew that they were an important component of aquatic ecosystems, but I didn’t understand quite how important. And while I’ve spent countless hours searching for and identifying species of many other taxa, from birds to bugs to plants, mussels never captured my interest. Now that I’m fully immersed in mussel ecology, however, I am definitely gaining some more respect for these underrated invertebrates.

Freshwater mussels are one of the most imperiled taxa in the country. According to Patty Morrison, a mussel expert and biologist at the Ohio River Islands National Wildlife Refuge, 76 out of the approximately 300 native mussel species in the U.S. are federally listed, six of which have been listed within just the past two years.

|

| Biologists Patty Morrison and Craig Zievis from Ohio River Islands NWR tagging mussels off the Missisquoi River. Credit: Ken Sturm, Missisquoi NWR manager. |

It’s important that we work to conserve them because of the crucial yet often overlooked services they provide. Individuals can filter several gallons of water per day, and thousands upon thousands of gallons over their lives, removing pollutants and purifying our water bodies in the process. If we started losing our mussel species, you can be sure there would be a noticeable decline in water quality.

And for those who still don’t appreciate mussels for their inherent value, they should at least be appreciated for their names! Mussels have been given some of the goofiest common names out there, including monkeyface, fat pocketbook, heelsplitter, strange floater, and orangefoot pimpleback, to name a few.

In late July, I had the privilege of assisting with a mussel survey and relocation project within the Missisquoi National Wildlife Refuge in northern Vermont. This work was necessary because a small section of the Missisquoi River required dredging so that a barge could be moved from bank to bank. Since Vermont state-listed mussel species were known to occur in the area, they had to be removed from the project area and relocated before the dredging could begin.

|

| Mussel biologists in action. Credit: Ken Sturm, Missisquoi NWR manager. |

Our intrepid team of biologists, led by Patty Morrison, carefully combed the sediments of the project area, including upstream and downstream buffer zones, which covered just over a fifth of an acre. We had to work slowly and cover the same ground multiple times because the density of mussels was so high in some places and because there were many small, young individuals that were easy to miss.

“The survey team was very diligent in their searching, especially when you consider that they were able to detect mussels as small as 4 mm in length,” Patty said afterwards.

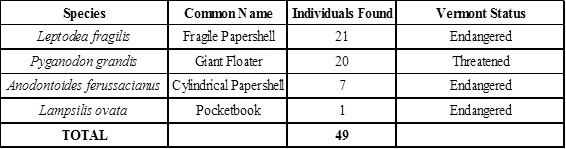

After three days of mussel hunting, we rounded up a whopping 808 individuals representing eight species. Eastern elliptio (Elliptio complanata) was the most abundant species with 522 individuals while eastern lampmussel (Lampsilis radiata), with 234 individuals, was the second most common. Together, these species made up 94 percet of the mussels we encountered. Of special interest were the four Vermont state listed species we found (see table below):

These 49 individuals were tagged and relocated to an underwater “corral” that will be monitored after the dredging project.

I found this to be very, very rewarding work. Although mussels aren’t exactly cute and cuddly animals, it still felt good to help save several hundred of them, including quite a few that are threatened or endangered in the state of Vermont. Unlike most cute and cuddly species, mussels are completely helpless, meaning putting in the man hours to get them out of harm’s way is that much more important. So not only did I gain a greater appreciation for mussels, but I also gained a greater level of respect for those who work hard to protect them.

Check out another blog post by Brett, or his New England Nature Blog, to read more about his work and interests.

No comments:

Post a Comment